Death Under Glass

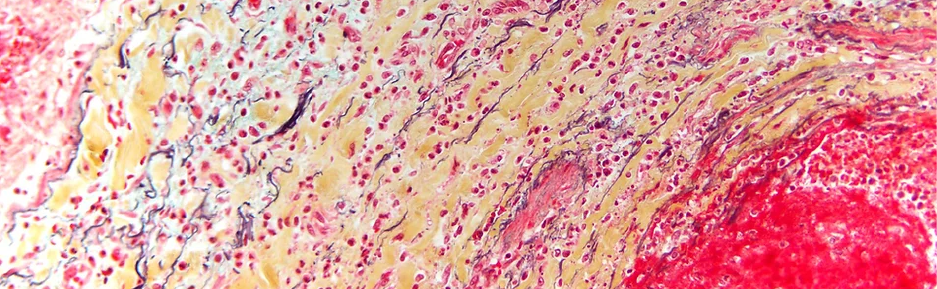

A glimpse of a rarely seen world: photographs of human cells at high magnification. Death Under Glass is a unique collaboration between forensic pathologist Marianne Hamel MD, PhD, and forensic photographer Nikki Johnson, MFA. The exhibition has traveled internationally since it was first shown at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia in 2014; this version of Death Under Glass will be the most extensive yet. Forensic pathologists investigate the images to determine a cause of death; for us, they are simply beautiful, illustrating the complex interplay of tissues in the human body.

Death Under Glass is on view in the Stedman Gallery at Rutgers University-Camden from September 5th until December 9th, 2023.